Recently a new drug to extend lifespan was granted conditional approval by the FDA–the first drug ever formally approved to extend lifespan! (By the way, the entrepreneur behind this breakthrough, Celine Halioua, is an emergent ventures winner for her earlier work rapidly expanding COVID testing. Tyler knows how to spot Talent!) Great news, right? Yes,

The post Conditional Approval for Human Drugs appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Recently a new drug to extend lifespan was granted conditional approval by the FDA–the first drug ever formally approved to extend lifespan! (By the way, the entrepreneur behind this breakthrough, Celine Halioua, is an emergent ventures winner for her earlier work rapidly expanding COVID testing. Tyler knows how to spot Talent!)

Great news, right? Yes, but there are two catches. First catch: the drug is for extending the lifespan of dogs. Second catch: Conditional approval is only available for animal drugs. Conditional approval was permitted for animal drugs beginning in 2004 for minor uses and/or minor species (fish, ferrets etc.) and then expanded in 2018 to include major uses in major species. What does conditional approval allow?

Conditional Approval (CA) allows potential applicants (referred to from this point as “sponsors”) to make a new animal drug product commercially available after demonstrating the drug is safe and properly manufactured in accordance with the FDA approval standards for safety and manufacturing, but before they have demonstrated substantial evidence of effectiveness (SEE) of the conditionally approved product. Under conditional approval, the sponsor needs to demonstrate reasonable expectation of effectiveness (RXE). A drug sponsor can then market a conditionally approved product for up to five years, through annual renewals, while collecting substantial evidence of effectiveness data required to support an approval.

Here is where it gets even more interesting. Why does the FDA say that conditional approval is a good idea?

First, it’s very expensive for a drug company to develop a drug and get it approved by FDA. Second, the market for a MUMS [Minor Use, Minor Species, AT] drug is too small to generate an adequate financial return for the company. The combination of the expensive drug approval process and the small market often makes drug companies hesitant to spend a lot of resources to develop MUMS drugs when there is so little return on their investment.

By allowing a drug company to legally market a MUMS drug early (before it is fully approved), conditional approval makes the drug available sooner to be used in animals that may benefit from it. This early marketing also helps the company recoup some of the investment costs while completing the full approval.

…Similar to conditional approval for MUMS drugs, the goal of expanded conditional approval is to encourage drug companies to develop drugs for major species for serious or life-threatening conditions and to fill treatment gaps where no therapies currently exist or the available therapies are inadequate.

Sound familiar? These are exactly some of the points that I have been raising about the FDA approval process for years. In particular, by bringing forward marketing approval by up to 5 years, conditional approval makes it profitable to research and develop many more new drugs.

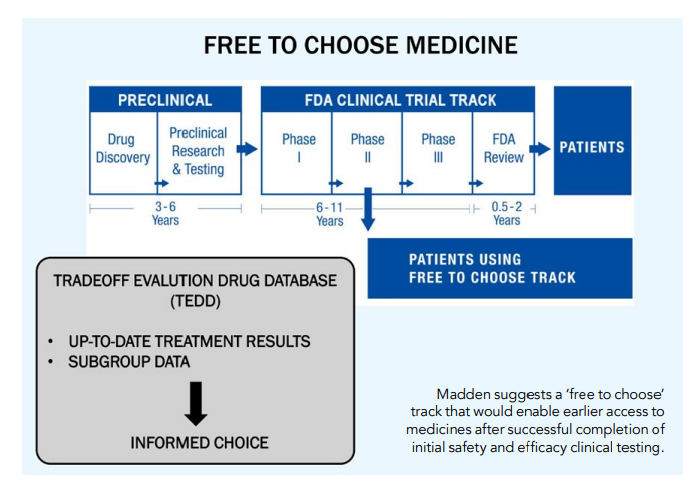

Conditional approval is very similar to Bart Madden’s excellent idea of a Free to Choose Medicine track, with the exception that Madden makes the creation of a public tradeoff evaluation drug database (TEDD) a condition of moving to the FTCM track. Thus, FTCM combines conditional approval with the requirement to collect and make public real-world prescribing information over time.

But why is conditional approval available only for animal drugs? Conditional approval is good for animals. People are animals. Therefore, conditional approval is good for people. QED.

Ok, perhaps it’s not that simple. One might argue that allowing animals to use drugs for which there is a reasonable expectation of effectiveness but not yet substantial evidence of effectiveness is a good idea but this is just too risky to allow for humans. But that cuts both ways. We care more about humans and so don’t want to impose risks on them that we are willing to impose on animals but for the same reasons we care more about improving the health of humans and should be willing to risk more to save them (Entering a burning building to save a child is heroic; for a ferret, it’s foolish.)

I think that the FDA’s excellent arguments for conditional approval apply to human drugs as well as to (other) animal drugs and even more so when we recognize that human beings have rights and interests in making their own choices. The Promising Pathways Act would create something like conditional approval (the act calls it provisional approval) for drugs treating human diseases that are life-threatening so there is some hope that conditional approval for human drugs becomes a reality.

Dare I say it, but could the FDA be lumbering in the right direction?

The post Conditional Approval for Human Drugs appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Uncategorized

Leave a Reply