[[{“value”:”The UK’s Orwellian sounding Equality Act 2010 is strikingly Marxist. It demands equal pay for work of equal value where these are defined as follows: A’s work is equal to that of B if it is like B’s work, rated as equivalent to B’s work, or of equal value to B’s work. A’s work is

The post Equality Act 2010 appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.”}]]

The UK’s Orwellian sounding Equality Act 2010 is strikingly Marxist. It demands equal pay for work of equal value where these are defined as follows:

A’s work is equal to that of B if it is like B’s work, rated as equivalent to B’s work, or of equal value to B’s work.

A’s work is like B’s work if A’s work and B’s work are the same or broadly similar, and such differences as there are between their work are not of practical importance in relation to the terms of their work.

…A’s work is rated as equivalent to B’s work if a job evaluation study— gives an equal value to A’s job and B’s job in terms of the demands made on a worker

…A’s work is of equal value to B’s work if it is neither like B’s work nor rated as equivalent to B’s work, but nevertheless equal to B’s work in terms of the demands made on A by reference to factors such as effort, skill and decision-making.

In short, supply and demand have been replaced by judges and labor boards with the authority to deem which jobs are “equal” and therefore should be paid equally. And the labor boards do so based on vague and subjective considerations that do not change with changing circumstances. Imagine replacing “jobs” with “condiments” and having judges decide whether ketchup and mustard should be priced equally because they are similar, broadly comparable, or rated equivalent in terms of the effort, skill, and decision-making that went into their production.

You think I am joking. I am not. Here’s an example of a case just decided in the UK.

More than 3,500 current and former workers at Next have won the final stage of a six-year legal battle for equal pay.

An employment tribunal said store staff, who are predominantly women, should not have been paid at lower rates than employees in warehouses, where just over half the staff are male.

The tribunal ruled that retail workers and warehouse workers were “equal” and thus had to be paid equally. Next replied that they paid everyone market wages. Verboten!

Next argued that pay rates for warehouse workers were higher than for retail workers in the wider labour market, justifying the different rates at the company.

But the employment tribunal rejected that argument as a justification for the pay difference.

According to the tribunal’s ruling, between 2012 and 2023, 77.5% of Next’s retail consultants were female, while 52.75% of warehouse operators were male.

The tribunal accepted that the difference in pay rates between the jobs was not down to “direct discrimination”, including the “conscious or subconscious influence of gender” on pay decisions, but was caused by efforts to “reduce cost and enhance profit”.

It ruled that the “business need was not sufficiently great as to overcome the discriminatory effect of lower basic pay”.

No one is alleging that male and female warehouse workers were paid unequally or that male and female retail workers were paid unequally or that there was any direct or indirect discrimination. The only claim is that warehouse workers, who are less likely to be female than retail workers, earn more than retail workers. And since these jobs have been judged “equal,” the company has violated Equality Act 2010.

Who could have predicted that jobs as disparate as warehouse and retail jobs might one day be deemed “equal.” Yet because Next failed to foresee such lunacy they are now required to pay millions in back wages to their retail employees. Software engineers, particularly in AI, are currently in high demand. A British firm looking to hire them may hesitate to raise wages, fearing that a future ruling could classify software engineers as “equal” to a larger, lower-paid group like HR administrators. Such a decision could easily push the firm into bankruptcy.

The warehouse workers were almost 50% female (47.25%). So females were not barred from the higher paying jobs. The fact that 77.5% of the retail workers were female suggests that retail work has special appeal to females relative to males and thus that there are compensating differentials. Any of the three female plaintiffs could have taken jobs in the warehouse. If the jobs are equal and the warehouse jobs pay more this is, on the plaintiffs’ theory, “puzzling”. [Or, as Ayn Rand would say, blank out.]

In fact, the court case reveals that Next was struggling to fill the warehouse positions and offered any retail employee—including the plaintiffs—the opportunity to switch to warehouse work. On cross-examination, one of the plaintiffs admitted that, given the unpleasant conditions in the warehouse—described by the court as “the drone of machinery,…vibration, alarm sirens and the screeching of machinery, wheels and rollers, continuously present in all areas”—the warehouse job “did not seem particularly attractive” compared to the greater autonomy and more appealing environment of the retail job. The plaintiff added that she would only have considered the warehouse job if it paid “a lot more money.”

Thank goodness for the men and women who were willing to take such jobs for only a little more money! It should not shock that different people have different preferences over jobs, just as they have different preferences over ice cream. In particular, it will perhaps surprise only the judges to learn that men tend to be more wage-focused and “women are relatively more attracted to employers with low pay but high values of nonpay characteristics (NBER 32408).” The court, however, recoiled from this idea, noting that if they were to take demonstrated preferences seriously this would be tantamount to applying “an unfettered free market model of supply and demand.” The horror.

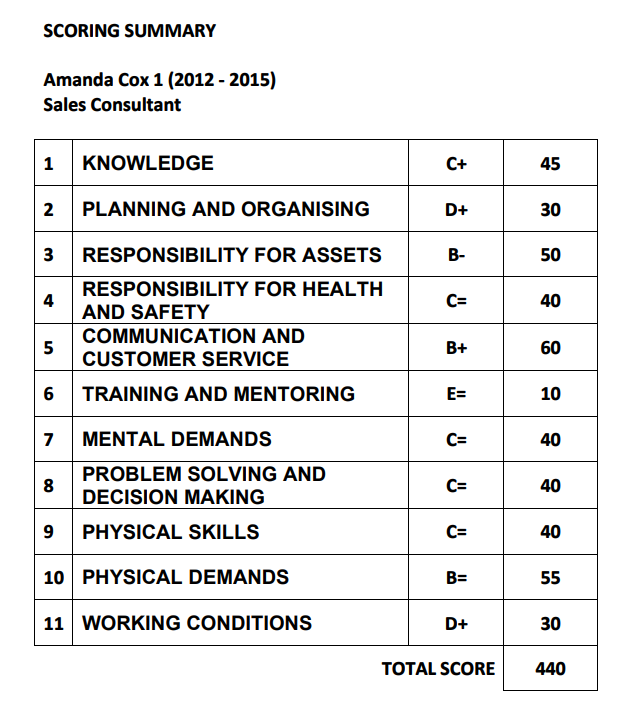

Now consider how the jobs were deemed “equal”. On the left is the job evaluation report for claimant Amanda Cox. The specific categories and numbers are not important; what is important is that the jobs are rated across 11 categories, and the point-scores are then added to get a total score at the bottom.

Amusingly, the evaluators emphasize that they use equal weighting across the categories. Of course, they did—because “equal” is synonymous with fair, right? An unequal weighting would surely be discriminatory!

I am not making this up:

Any scheme which has as its starting point – “This qualification is paramount” or that “This skill is vital” is nearly always going to be biased or at least open to charges of bias or discrimination.

Thus, if you think that a skill is vital for a job, that’s discrimination!

(Notice also that equal weighting is just another form of weighting. Given the subjective nature of both the categories and the points assigned, equal weighting holds no inherent superiority or objectivity.)

But no matter—we have yet to get to the best part. The evaluators selected three warehouse workers and assessed them using the same metric. For example, Amanda Cox was compared to warehouse worker Calvin Hazelhurst, resulting in the table on the right.

Can you spot something surprising in this table? I’ll give you a moment.

The obvious conclusion any reasonable person would draw from this table is that the jobs are clearly not equal. Amanda’s total score is 440, while Calvin’s is 340. 440 ≠ 340. Not even close! In nearly every category—except (no surprise!) physical demands and working conditions—the retail job requires more points, aka “skill and responsibility”.

At this point, most people would stop and ask some critical questions. If the jobs differ so much across multiple dimensions, isn’t it clear that they are not equal? And why do jobs that seemingly require less “skill” pay more? Could it be that our point-score rating system is oversimplified? Maybe the market is telling us something that this crude scoring system isn’t capturing? Is it time to check our premises?

But not the evaluators! Oh, no. The evaluators are thrilled–because the fact that the jobs are unequal proves that they are equal!

War is peace, freedom is slavery, ignorance is strength. UNEQUAL IS EQUAL.

Adam Smith had a much better understanding of wages in 1776 than UK judges have today.

The wages of labour vary with the ease or hardship, the cleanliness or dirtiness, the honourableness or dishonourableness, of the employment. Thus in most places, take the year round, a journeyman tailor earns less than a journeyman weaver. His work is much easier. A journeyman weaver earns less than a journeyman smith. His work is not always easier, but it is much cleanlier. A journeyman blacksmith, though an artificer, seldom earns so much in twelve hours, as a collier, who is only a labourer, does in eight. His work is not quite so dirty, is less dangerous, and is carried on in day-light, and above ground. Honour makes a great part of the reward of all honourable professions. In point of pecuniary gain, all things considered, they are generally under-recompensed, as I shall endeavour to shew by and by. Disgrace has the contrary effect. The trade of a butcher is a brutal and an odious business; but it is in most places more profitable than the greater part of common trades. The most detestable of all employments, that of public executioner, is, in proportion to the quantity of work done, better paid than any common trade whatever.

Today, the UK would convene a labor board to rule that the tailor and the weaver must be paid equally because they DO WORK OF EQUAL VALUE. Case closed.

Labor boards will inevitably lead to the misallocation of labor, diminishing both wealth and fairness. Severe misallocation may lead to further intervention, in the worst scenario, even to the allocation of labor by fiat. Politicization breeds division, rent-seeking, and a stagnant, unpleasant society.

More generally, it pains me that there is no recognition that the market is a discovery procedure, including the discovery of the value of different skills and people’s preferences over different jobs. No recognition that the market harnesses tacit knowledge and knowledge of particular circumstances of time and place–knowledge that is difficult to quantify, communicate, or communicate in a timely manner–and that “society’s economic problems are primarily related to adapting quickly to changes in these circumstances.” No recognition that a price is a signal wrapped up in an incentive.

I despair when I consider that these fundamental ideas are the foundation of our liberal, global, and prosperous civilization. On economics, as on free speech, the UK has entered the great forgetting.

Addendum: A special hat tip to Bruce Greig who brought this to my attention and had the receipts.

The post Equality Act 2010 appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Current Affairs, Economics, Law, Political Science, Equality Act of 2010

Leave a Reply