[[{“value”:”It’s long been argued that the means of production influence social, cultural and psychological processes. Rice farming, for example, requires complex irrigation systems under communal management and intense, coordinated labor. Thus, it has been argued that successful rice farming communities tend to develop people with collectivist orientations, and cultural ways of thinking that emphasize group

The post Cultivating Minds: The Psychological Consequences of Rice versus Wheat Farming appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.”}]]

It’s long been argued that the means of production influence social, cultural and psychological processes. Rice farming, for example, requires complex irrigation systems under communal management and intense, coordinated labor. Thus, it has been argued that successful rice farming communities tend to develop people with collectivist orientations, and cultural ways of thinking that emphasize group harmony and interdependence. In contrast, wheat farming, which requires less labor and coordination is associated with more individualistic cultures that value independence and personal autonomy. Implicit in Turner’s Frontier hypothesis, for example, is the idea that not only could a young man say ‘take this job and shove it’ and go west but once there they could establish a small, viable wheat farm (or other dry crop).

There is plenty of evidence for these theories. Rice cultures around the world do tend to exhibit similar cultural characteristics, including less focus on self, more relational or holistic thinking and greater in-group favoritism than wheat cultures. Similar differences exist between the rice and dry crop areas of China. The differences exist but is the explanation rice and wheat farming or are there are other genetic, historical or random factors at play?

A new paper by Talhelm and Dong in Nature Communications uses the craziness of China’s Cultural Revolution to provide causal evidence in favor of the rice and wheat farming theory of culture. After World War II ended, the communist government in China turned soldiers into farmers arbitrarily assigning them to newly created farms around the country–including two farms in Northern Ningxia province that were nearly identical in temperature, rainfall and acreage but one of the firms lay slightly above the river and one slightly below the river making the latter more suitable for rice farming and the former for wheat. During the Cultural Revolution, youth were shipped off to the farms “with very little preparation or forethought”. Thus, the two farms ended up in similar environments with similar people but different modes of production.

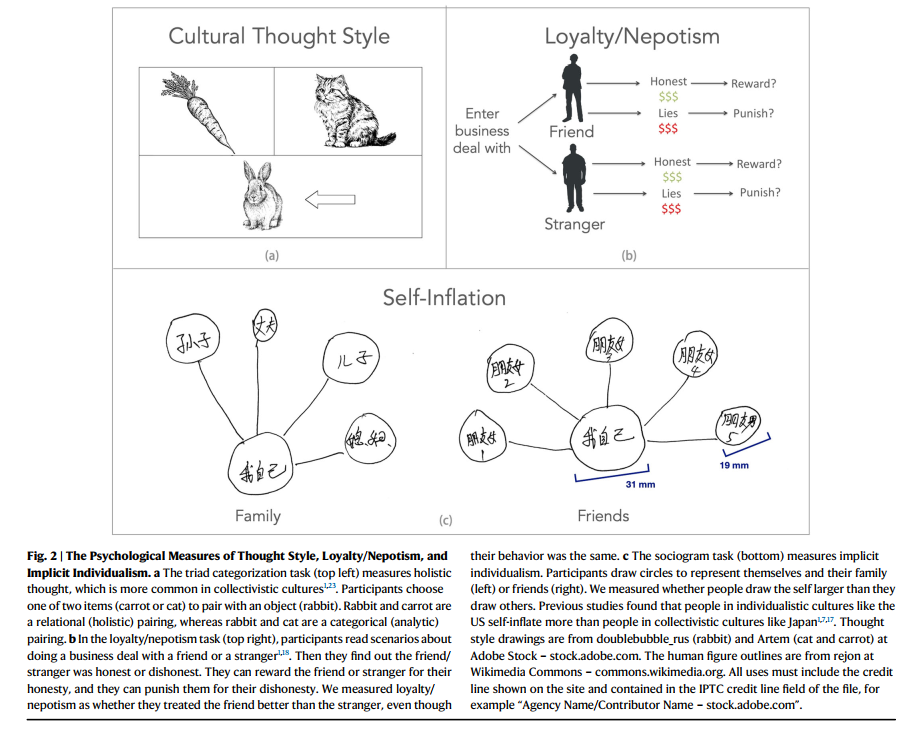

Talhelm and Dong measure thought style with a variety of simple experiments which have been shown in earlier work to be associated with collectivist and individualist thinking. When asked to draw circles representing themselves and friends or family, for example, people tend to self-inflate their own circle but they self-inflate more in individualist cultures.

The authors find that consistent with the differences across East and West and across rice and wheat areas in China, the people on the rice farm in Ningxia are more collectivistic in their thinking than the people on the wheat farm.

The differences are all in the same direction but somewhat moderated suggesting that the effects can be created quite quickly (a few generations) but become stronger the longer and more embedded they are in the wider culture.

I am reminded of an another great paper, this one by Leibbrandt, Gneezy, and List (LGL) that I wrote about in Learning to Compete and Cooperate. LGL look at two types of fishing villages in Brazil. The villages are close to one another but some of them are on the lake and some of them are on the sea coast. Lake fishing is individualistic but sea fishing requires a collective effort. LGL find that the lake fishermen are much more willing to engage in competition–perhaps having seen that individual effort pays off–than the sea fishermen for whom individual effort is much less efficacious. Unlike Talhelm and Dong, LGL don’t have random assignment, although I see no reason why the lake and sea fishermen should otherwise be different, but they do find that women, who neither lake nor sea fish, do not show the same differences. Thus, the differences seem to be tied quite closely to production learning rather than to broader culture.

How long does it take to imprint these styles of thinking? How long does it last? Is imprinting during child or young adulthood more effective than later imprinting? Can one find the same sorts of differences between athletes of different sports–e.g. rowing versus running? It’s telling, for example, that the only famous rowers I can think are the Winklevoss twins. Are attempts to inculcate these types of thinking successful on a more than surface level. I have difficulty believing that “you didn’t build that,” changes say relational versus holistic thinking but would styles of thinking change during a war?

The post Cultivating Minds: The Psychological Consequences of Rice versus Wheat Farming appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Economics, History, Philosophy, Religion, Science

Leave a Reply