[[{“value”:”In the 1970s the general aviation aircraft industry was selling 15,000 or more aircraft a year but that number fell by a factor of about 10 in the early 1980s. What happened? One factor was a massive increase in tort liability as discussed in my paper with Eric Helland, Product Liability and Moral Hazard: Evidence

The post Why Don’t We Have Flying Cars? appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.”}]]

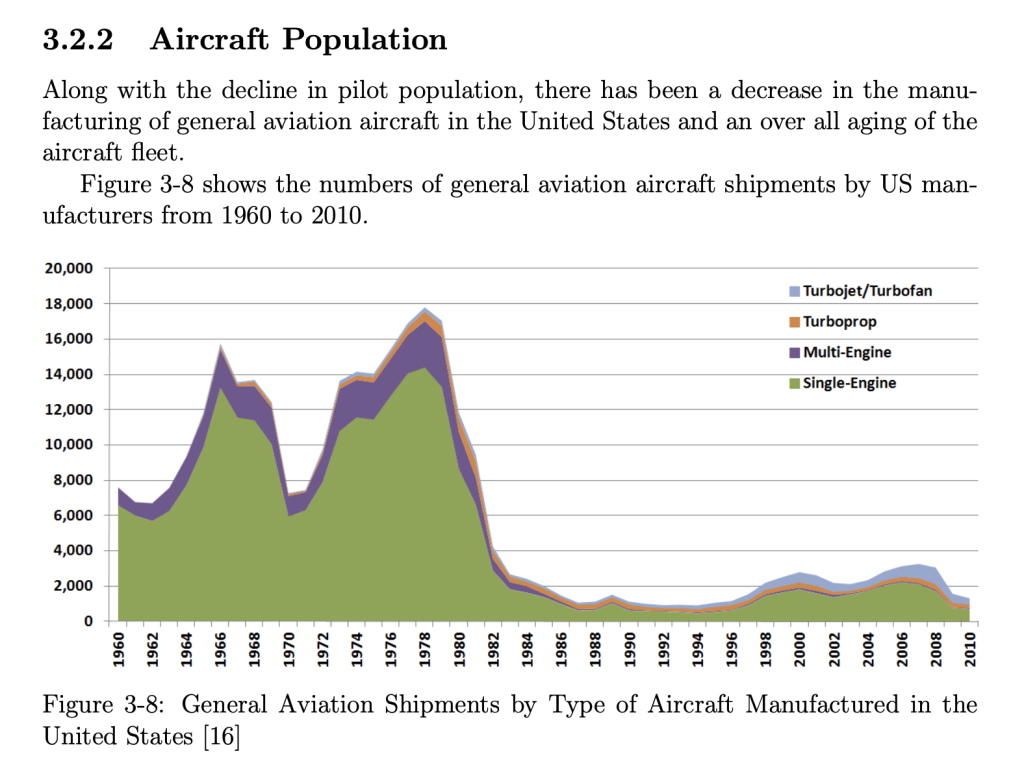

In the 1970s the general aviation aircraft industry was selling 15,000 or more aircraft a year but that number fell by a factor of about 10 in the early 1980s. What happened? One factor was a massive increase in tort liability as discussed in my paper with Eric Helland, Product Liability and Moral Hazard: Evidence from General Aviation. Another factor was ever-increasing FAA regulation.

But Max Tabarrok raises an interesting puzzle. It’s not at all obvious that the regulation of personal aircraft has been more strict than that of automobiles. So why the big difference in outcomes? There is, however, one small but potentially very important difference between the regulation of cars and aircraft.

By far the costliest part of the FAA’s regulation is not any particular standard imposed on pilot training, liability, or aircraft safety, but a slight shift in the grammatical tense of all these rules. The Department of Transportation (DOT) sets strict safety requirements for cars, but manufacturers are allowed to release new designs without first getting the DOT to sign off that all the requirements have been satisfied. The law is enforced ex post, and the government will impose recalls and fines when manufacturers fail to follow the law.

The FAA, by contrast, enforces all of its safety rules ex ante. Before aircraft manufacturers can do anything with a design, they have to get the FAA’s signoff, which can take more than a decade. This regulatory approach also makes the FAA far more risk-averse, since any problems with an aircraft after release are blamed on the FAA’s failure to catch them. With ex post enforcement, the companies that failed to follow the law would be blamed, and the FAA rewarded, for enforcing recall.

This subtle difference in the ordering of legal enforcement is the major cause of the stagnation of aircraft design and manufacturing.

In some ways, this is an optimistic message, since it illuminates an attractive political compromise: keep all of the safety standards on airplanes exactly as they are, but enforce these standards like they’re enforced with cars—i.e., through post-market surveillance, recall, and punishment. This small change would reinvigorate the general aviation industry, putting it back on the exponential trend upwards that it lost 50 years ago.

The post Why Don’t We Have Flying Cars? appeared first on Marginal REVOLUTION.

Economics, Travel

Leave a Reply